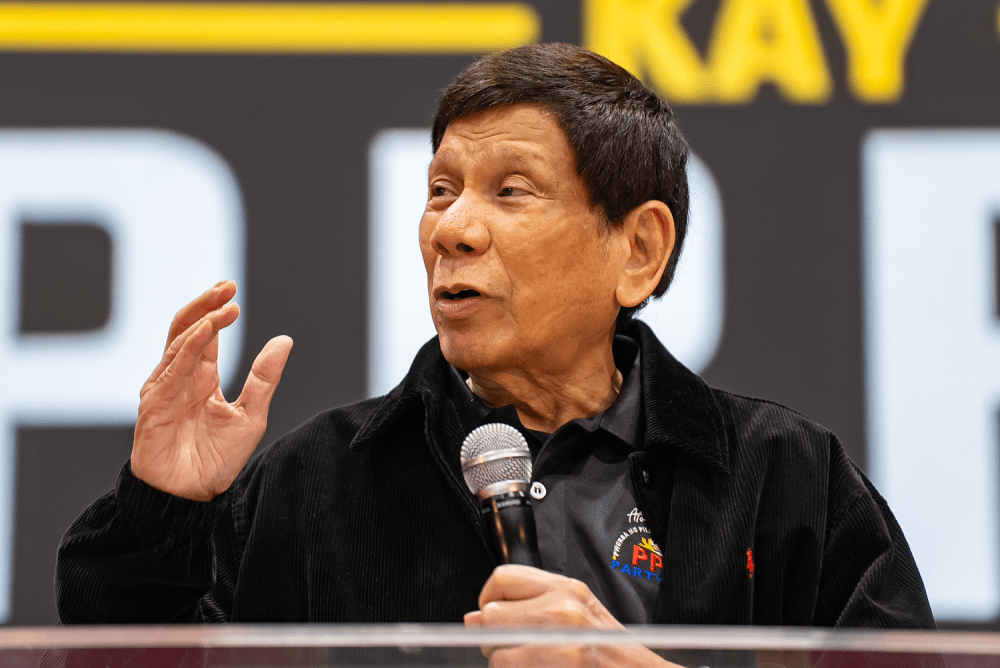

The arrest of former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte on March 11, on a warrant issued by the International Criminal Court (ICC), already feels like a seismic event. It’s a startling fall from grace for a leader who, just a few short years ago, was the country’s most popular politician and stood on the verge of creating a familial dynasty.

Instead, Duterte found himself on board a jet en route to The Hague, having been outflanked by President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in an explosive power struggle.

It’s an exceedingly rare case of the international justice system holding a strongman accountable. Duterte, 79, will be the first former leader from Asia to go on trial at the ICC. Within the Philippines, families of drug war victims have waited years for the leader known as “the Punisher” to face justice.

Marcos Jr. said on March 11 that Duterte would face “charges of crimes against humanity in relation to his bloody war on drugs.”

“Interpol asked for help, and we obliged,” he said at a press conference. “This is what the international community expects of us as the leader of a democratic country.”

Duterte was apprehended on March 11 after arriving from Hong Kong at Manila’s Ninoy Aquino International Airport. Rumors had swirled for days that the ICC would issue the warrant, concluding a yearslong investigation into his deadly anti-drug campaign, in which thousands of drug users and low-level dealers were extrajudicially killed by police and hired hitmen.

Official figures say around 6,200 people have been killed in Duterte’s war on drugs, although rights groups put that number much higher; the ICC prosecutor estimates it may exceed 30,000.

Duterte withdrew the Philippines from the ICC in 2018, after the prosecutor announced a preliminary investigation into his war on drugs, and he has repeatedly taunted the ICC ever since.

Duterte truly became vulnerable after he began feuding with Marcos, who rose to power in 2022 after forming an alliance with Duterte’s daughter, Sara, who ran for vice president and still holds that office. (While the president and vice president are elected separately, Marcos and Sara Duterte ran as a de facto joint ticket.) Their alliance fractured last year, spiraling into a bitter feud between the current president and former one. Marcos is the son of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. Sara Duterte is now facing an impeachment probe ahead of the country’s upcoming regional and parliamentary elections.

“If the Marcos-Duterte alliance didn’t break to begin with, none of this would have happened,” said Carlos Conde, a senior researcher at the Asia Division of the Human Rights Watch.

The alliance began to fray last year when Duterte started criticizing Marcos, perhaps wary that Marcos would endorse an ally, rather than his daughter, to succeed him in 2028.

Domestic political winds began to shift toward Marcos when public attention turned to the country’s maritime conflict in the South China Sea, where the Chinese military has aggressively confronted Philippine fishermen and blocked resupply missions. Marcos has defended Philippine sovereignty in the contested waters, which Beijing claims as its own despite a 2016 international tribunal ruling favoring Manila.

As president, Duterte warmed to China and did not challenge its presence in Philippine waters, and his family and political allies have been dogged by alleged links to Beijing.

It has led to a strange convergence of interests between Marcos, the ICC, and the families of drug war victims who had “lost faith in the domestic criminal justice system,” Conde said.

Marcos has not exactly been a reformer himself. He made it clear that the Philippines was cooperating with Interpol, not the ICC, which he has taken no steps to rejoin. Under his watch, drug war killings have continued, albeit at a much lower rate, and activists still face harassment and forced disappearances.

“All of this rhetoric about the Marcos administration being a different administration than Duterte is that it has a much more respectful stance toward human rights,” Conde said. “This is the opportunity for Marcos to prove that.”

Indeed, the Marcos administration has been nothing like the bloodiest years of Duterte, when he vowed to fill Manila Bay with the bodies of drug users and threatened to arrest or kill anyone who crossed him. In 2017, Sen. Leila de Lima, a leading critic of Duterte’s drug war, was arrested on fabricated drug charges. The last charges against her were dismissed by Philippine courts last year.

De Lima said that Duterte’s arrest would end impunity in the Philippines. She also acknowledged that it would be difficult for the families of drug war victims to bring cases against members of the Philippine National Police. So far, only eight officers have been convicted of drug-related killings.

“The [Philippine National Police] did not investigate the killings because they were the killers,” de Lima said. “This means no evidence was gathered so it will be difficult to build individual cases against individual policemen.”

According to de Lima, it would be easier to bring civil cases, which have a lower burden of evidence. “The victims should attempt to file cases even against the government itself for monetary compensation,” she said, suggesting that they push for a compensation law similar to one that was passed for victims of martial law under Marcos Sr.

“What are urgently needed are laws that will rebuild and strengthen institutions to make sure that they can withstand the next time another Duterte comes along to cause mayhem,” de Lima said.

Building those institutions will still require navigating a government packed with supporters or onetime allies of Duterte, many of whom still make up the political coalition that Marcos himself depends on.

“Duterte’s allies and progenies still hold considerable political power,” said Joel Ariate, the lead researcher for the Dahas Project, an initiative of the University of the Philippines that tracks drug-related casualties.

Several Duterte allies are now serving as senators, including former police chief Ronald “Bato” Dela Rosa, who oversaw the bloodiest portion of the drug crackdown, and former presidential assistant Christopher “Bong” Go, who became meme fodder after unsuccessfully trying to deliver a pizza to Duterte as he was taken into custody. Both men are running for reelection in May.

Duterte himself is still running for mayor in his hometown of Davao, where his family has controlled politics for more than three decades. Unless he is disqualified, he is almost certain to win the seat.

His children have already made false claims that their father was wrongfully arrested and mistreated while in custody, setting the stage for further clashes ahead of the May elections. Aside from Sara, his sons Paolo and Sebastian serve in the Philippine House of Representatives and as mayor of Davao, respectively.

ICC trials are lengthy, brooding affairs. Duterte, already aging and with health concerns, could sit in The Hague for years, where he may become viewed by supporters as a martyr. His lawyers have demanded his return to the Philippines, accusing the government of “kidnapping” him.

“Duterte’s arrest will no doubt solidify support for him and his political allies,” Ariate said.

Reports from the Dahas Project show that drug war killings have continued under Marcos, shifting mainly to the central city of Cebu, where contract killers, not police, are culpable for almost all of the killings. But even as state agents are less involved in drug killings, the culture of impunity that Duterte once championed remains entrenched.

“The killings will stop,” Ariate said, “if the Marcos government wants it to stop.”